They may be high up, but numbers are crashing to Earth. A family of giraffes stares down at the strange human lying in front of them

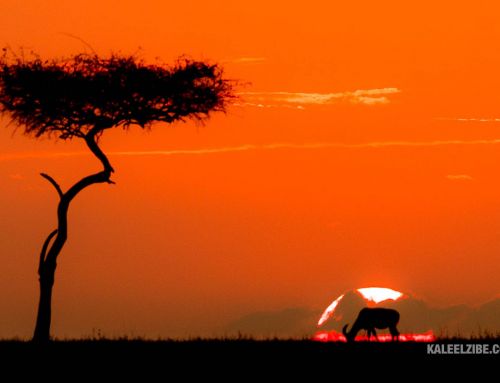

Serene silhouette

How d’you know you’re looking at a male giraffe? He’s got a big knob on his head. Yup.

Frivolity aside (although the knob thing is actually true), these creatures are awe-inspiring when studied at close quarters. If you’ve only ever seen giraffes in a zoo, nothing will prepare you for how other they are in the wild. That ridiculously tall neck. The legs. The knees! And also how you really can lose a six metre tall, one ton beast even though it’s right in front of you. I’ve had several encounters with giraffes, but let me tell you about three that I’ll remember for ever.

First off, on our 2015 safari, I had an unusual opportunity to get out of the vehicle to photograph a family of giraffes from ground level. Our group had spent a long while photographing the animals from the vehicle and had mostly exhausted the available shots when our Maasai guide, Moses suggested it would be ok for me to get out of the Land Cruiser and creep under the front wheel for a unique angle. Most animals more or less ignore you when you’re in a vehicle. They either assume you’re part of the vehicle, or just don’t see you as a threat / lunch. However, as soon as you exit, they see you differently and react. In this instance, I thought I’d done a stealthy slink out on the giraffes’ blind side and snuck under the wheel slowly and quietly, unnoticed. But the game was up immediately. Wild animals aren’t stupid and a whole forest of necks turned and levelled an imperious stare at the idiot photographer prostrate on the ground in front of them. Happily, they weren’t spooked and stood like blotchy statues while I got some photographs with a nice low perspective. Meanwhile Moses and my other companions in the vehicle scanned for bitey cats and hyenas. I don’t think anyone else fancied running the gauntlet!

The invisible giraffe

The second encounter was several years ago in Zimbabwe when driving through a highly unpromising piece of scrubby woodland. It was one of those occasions where you assume nothing interesting will happen because of the terrain and set about cleaning the dust off your lens or (finally) remembering to apply some sun cream to gently sizzling bits of forehead. A few minutes into the scrub, we stopped. I looked around: nothing but dry trees. Why would we stop here? “Giraffes” came the answer. Where? Oh…

This is why you need safari guides who can spot a lion killing a warthog 2 miles away, or a secretary bird stalking on the far side of a plain. Otherwise you’d be blissfully ignorant of some of the best opportunities. Following my guide’s finger, my gaze alighted abruptly on a giraffe. A giraffe that definitely hadn’t been there a second before. But how could such a large animal hide in plain sight? The camouflage was uncanny. Not only that, but once I got my eye in, I discovered there was a whole herd right under our noses: a family of at least eight surrounding us, quietly browsing leaves and gently gliding through the bush without a sound. What a moment. What majesty and elegance these animals have. They may seem ungainly in captivity, but in the wild, they are graceful. I don’t remember breathing out, but I must have, eventually.

A baby giraffe greets its mother

The last special giraffe memory I’d like to tell you about happened near the end of last year’s trip to Kenya. We’d seen plenty of giraffes, but on the way home to the camp, anticipating a glass of red wine with friends round the camp fire, we came across a baby giraffe with its mother. At first sight, it didn’t look like a baby: it was taller than I am and was running significantly faster than I can (ok, giraffes can run very fast, and I’m rubbish at running). The give-away was the still visible dried umbilical cord. This unexpectedly cute giant, gleefully sprinting around after its mother for the sheer fun of it, was only a few days old and had actually been born during our stay in the Masai Mara. It hadn’t been there when we arrived at House in the Wild eight days earlier. What a privilege to witness.

A privilege that my children’s children might not get to see.

Along with a number of high profile, iconic species around the world, giraffes are declining at an alarming rate: there are now only 97,000 giraffes in the wild. That’s 55,000 fewer than 30 years ago. To put it bluntly, they’re in short supply and at that rate, they might become extinct in the near future. The IUCN Red List has reclassified giraffes as ‘vulnerable’ after a nearly 40% reduction in numbers. The causes are the usual toxic mixture of poaching and habitat loss / degradation due to human encroachment, agriculture and industry, as well as war to mention just some of the factors. Giraffes and their close relatives, the endangered okapis are relatively poorly studied and receive limited conservation efforts and funding, but the IUCN World Conservation Congress drew up plans in September to attempt to reverse the decline.

I have a theory about the decline of such iconic animals as giraffes and lions and tigers and cheetahs et al. It goes something along the lines that we don’t actually believe an animal like the giraffe could possibly go extinct because photographs of these animals are so plentiful and ubiquitous and the creatures are so embedded in our consciousness that it’s impossible to connect with the notion that they might disappear entirely. That’s a dangerous assumption.

During my time in Kenya this year I made a short film about our wildlife experiences in the Masai Mara, which includes footage of giraffes. It’s unthinkable that in a few decades, there might be no more giraffes to film.

8-day old baby giraffe born during our time in Kenya

This is why acacia trees are shaped like this.

Knobbly knees contest winners

Giraffe family sunset

A sturdy, foot-long tongue enables these leviathans to pluck desert dates from between the acacia tree spines

Giraffes in their landscape

Leave A Comment