I’ve been a professional wildlife photographer since 2008 and for all of that time I’ve been trying to take pictures that will invoke an emotional response with people. In my experience, there is nothing that does that quite as well as baby animals. It’s probably got a lot to do with the cute factor.

I’ve collected here some of the baby animals and young wildlife photos that I’ve taken over the years. Each one of them triggers a fond memory and takes me back to where and when I took that photo. Whilst I’ve described a little about how to approach taking these shots below, this is perhaps less of a Tips blog post than a celebration of young wildlife. Having said that, there are one are two things that are worth noting about taking photographs of juveniles and baby animals and birds and it would be broadly covered under the heading of creating a disturbance to the animal at its most vulnerable. More of that in a minute.

What’s not to love about lion and leopard cubs?

It’s so rewarding to photograph and film young animals: they tend to be more playful and more cute than their parents. It’s often just a case of pointing your camera and waiting for them to do something funny or cute. All the usual rules of wildlife photography composition and camera settings apply just in the way that they would for adults, but one thing that I think often sets young animals apart from adults is that they are often really good for interactive shots because of that playfulness. Watching lion cubs or young elephants play-fighting is an absolute joy. And to photograph them doing that: even better.

Baby elephants play-fighting, young grey seals, an Arctic tern chick and a baby rabbit

One useful thing to note is that because young animals are usually much smaller than their parents, it’s worth making that connection in the photograph. So for example you might want to put a cute baby with its parent to show the different sizes and parental love and protection, rather than only taking photographs of the young animal by itself. Putting a parent in the frame also underlines how small the babies can be.

Some examples of young animals and birds with their parents: elephants, humpback whales, giraffes, zebras, grey seals, shags (the brown one is the baby), guillemots, Arctic terns and ostriches

Lastly, the prickly business of whether you should be taking the photo in the first place. This is particularly important to consider where the species is threatened or endangered. For these animals and birds, they need the utmost protection when at their most vulnerable, which is usually when they are very young and still at the nest / den etc. As such, they are often protected by laws and rules that stipulate when they can and can’t be approached – including to be photographed.

An example of this would be birds in the UK covered under Schedule 1 licenses: you would need one of these licenses to get anywhere near these creatures at their nest. The BTO issues licenses on behalf of Natural England. They also have a list that tells you which birds are protected and in which territories. These licenses are often called disturbance licenses because you are intentionally creating a disturbance at this species’ most vulnerable point by approaching them. Obviously, photographing the animals at this sensitive time is a disturbance too, particularly if you get close, as we often want to in photography for that special shot.

With endangered species, this is not only a risk for their survival (nest abandonment, behavioural change, increased risk of predation, etc.), but it is illegal and you could be prosecuted. So, the long and the short of it is that you need to know which species are vulnerable and protected before you even attempt to go and photograph them. Occasionally you may be allowed to photograph a sensitive species for a specific purpose if in the long run it does the conservation of that species some good.

For example, several years ago I did a project on red kites, which are protected birds. I was attached to the RSPB who were doing a project in our local area and was asked to take photographs at and near the nest sites of some of the kites. This could only be done under the supervision of the local RSPB team who had a Schedule 1 disturbance license. I was then allowed to photograph the nest site and young birds as long as I made myself scarce if anybody walked nearby and never disclosed to anybody where the nest was. I also ended up taking a photograph of a young kite that had fallen out of its nest and was being kept in an undisclosed location before being later released.

Red kite on a nest, photographed with a Schedule 1 license. The second photograph is the young kite that hatched from the egg you can just see in the first photo. It actually fell out of the nest and was rescued. After recuperation, I was allowed to photograph it before it was re-released into the wild

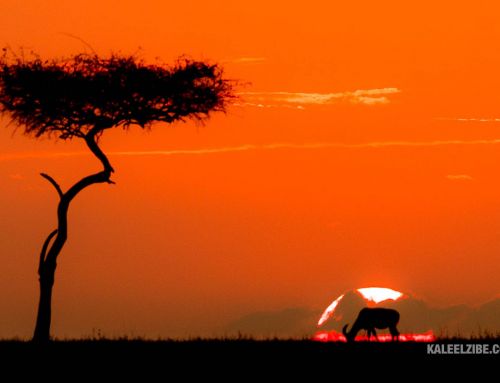

Similarly when photographing lion cubs or any other mammals in Africa, as I often do when taking people on photography safaris, I and all of the clients I take under my wing must always pay attention to what our guides tell us is possible. Sometimes they will say we must move away from an animal to avoid distress. This must be the baseline for all wildlife viewing, never mind photography. And it is particularly important where young animals are concerned.

All this being said, if you’ve done your research and you either know the species is not threatened, or you have the permission of a body who can grant you access, then carry on.

You may at this point be thinking, well there are plenty of garden birds or woodland animals that are not threatened that would be fair game to photograph when young. Just bear in mind that all animals when very young are vulnerable, even if the species itself is not protected. Always exercise caution and don’t get too close. Use your common sense: you can usually tell when wildlife feels under threat.

Hi,

Just came across your website, you have some amazing content and insights, I’ll definitely be reading through everything. Bookmarked to my browser homepage!

Thanks, Fiona. Glad you found it useful 🙂

Cheers,

Kaleel

Thank you for the lovely photos! It just brightens up ones day!

Thanks, Antoinette 😊